We encountered several types of gardens each of which had a different clientele and architectural setting: imperial gardens (Sadabad), gardens for the public (Kagithane), picturesque landscape gardens (Stourhead), commercial public gardens (Vauxhall, London and Vauxhall, New York), contemporary theme parks (Disneyland).

Sadabad built by Ahmet III and his grand-vizier Damat Ibrahim Pasha and the gardens of Kagithane. The division between the Sadabad garden and the public area was quiet porous. From, Hamadeh, The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eighteenth Century, figure 78 (Plate 1) from a copy of Enderunlu Fazil’s Zenanname.); figure 4. Engraving by l’Espinasse.

According to the Harwood piece, in the Dumbarton Oaks volume Theme Park Landscapes: Antecedents and Variations, picturesque landscape gardens may be considered as the social origins of contemporary theme parks while according to Schenker, in the same book, it is the commercial pleasure gardens, e.g. Vauxhall Gardens of New York, that gave inspiration to them. Nevertheless, Hamadeh’s account of Istanbul points to the fact that gardens for the public developed in tandem with the rise of a new “middle class,” and were shaped by the elite or royalty who opened old palatial gardens to public access, and nurtured the creation of new public spaces through their patronage.

After the takeover of Istanbul by Sultan Mehmed II, Ottoman sultans adopted a protocol of seclusion. Imperial excursions to suburban estates were one of the few occasions to see the sultan and his entourage. Starting in the early eighteenth century, Ottoman sovereignty forged itself a new image, based on visibility. This corresponds with the restoration of old gardens, the opening up of some for public use, and the creation of new gardens for the public, developments which were coupled by parallel attempts to monitor and control the public through sumptuary laws and new law enforcement personnel (e.g. the gardeners who increasingly policed the spaces under their control).

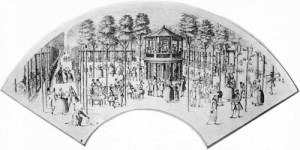

The Grove at Vauxhall Gardens with the Music Pavilion, and the Prince of Wales’s Pavilion, The Vauxhall Fan, ca. 1737.

J. S. Muller after Samuel Wale, A General Prospect of Vaux Hall Gardens, after 1751 (cal. no. 73). From, Vauxhall Gardens, edited by T. J. Edelstein. New Haven, Conn.: Yale Center for British Art, 1983.

Commercial pleasure gardens were surrounded by walls, and a nominal entry fee was charged at the entry gate. Further money was made through food and drink stalls. Supper boxes enabled consumption of food as well as privacy within public space. Changing programs of theatrical and musical performances were supplemented by changing décors of art works and theatrical settings—paintings, statues, fountains, ornamental arches, night illuminations, illusions including pyrotechnics, mechanical devices— using all of which proprietors sought sustained patron interest.

While there is a tendency to interpret the emergence of public gardens as the democratization or emulation of what was once in the purview of royalty and aristocracy, for instance to describe pleasure gardens such as Vauxhall as “an unashamedly commercial exploitation of a garden tradition hitherto available only to a select few, adapted and democratized by Tyers’ entrepreneurial talents to cater to the same expanding middle-class market that frequented the play houses north of the river,” (Allen, 17) together, these examples clearly show that that the trickle-down theory is limited. In many instances, it was rather members of royalty who adapted to popular urban practices by patronizing new public spaces as in the case of Prince Frederick who had his own pavilion in Vauxhall Gardens, depicted in the famous Vauxhall Fan. Perhaps more dramatic is the architectural transition in the palatine tradition of the Ottoman sultanate—from Topkapı Palace to Dolmabahçe Palace, with numerous summer palaces on the Bosphorus created for visual consumption by a broad public. In many instances, it was the palace that was emulating an urban architecture of an “exhibitionary nature” (Hamadeh, 135).

An “exhibitionary” architecture: Said Pasa Waterfront Mansion, Kandilli. Migirdic Civanyan’s copy of a plate in Thomas Allom’s book Constantinople and Scenery of Seven Churches of Asia Minor (published in 1839 in London) executed in the late 19th century.